The life of Corita Kent, a charismatic nun with the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, was filled with intriguing contradictions. She was a devout Catholic, a follower of the ancient church, and simultaneously a resident of the modern world. She had a deep love for life, yet felt profound sorrow over social injustice and poverty. For thirty-two years, she lived as a nun in Los Angeles, becoming a highly influential educator, graphic designer, activist, and pop artist. Although Kent was internationally famous during her lifetime, scholars only began to seriously examine her work in the 21st century. More at losangeleska.

Learn about the history of Los Angeles nun activists: protests and the power of community.

Biography

Frances Elizabeth Kent was born in Iowa in 1918 and moved with her family to Hollywood in 1923. Throughout her childhood, Kent was always drawn to creative design and sketching. She recalled always being “passionate about something,” whether it was designing clothes, making paper dolls, or drawing. Although she didn’t think much of her abilities, her parents and teachers immediately saw her talent.

Kent attended a Catholic elementary school and then a high school for girls run by the Immaculate Heart nuns in Hollywood. Kent later lamented that the older nuns’ approach to art classes was to have students copy the old masters. Even so, her artwork at school was praised for its originality. They saw great potential in Frances and encouraged her to pursue further studies in art.

She joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary at age eighteen, taking the name Sister Mary Corita. At the convent in Los Angeles, her artistic talent was noticed by one of the senior nuns, Magdalene Mary, who encouraged Kent to train as an art teacher. She subsequently went on to work at Immaculate Heart College—a liberal arts institution well-known for its avant-garde views—and became head of its art department in 1964. While pursuing a master’s degree in art history at the University of Southern California in 1951, Kent discovered screen printing (also known as serigraphy), the medium that would bring her to the art world’s attention.

She sought to create a new type of religious art, one that avoided the sentimental style popular at the time. She was also deeply interested in the art of her day, and her screen prints also demonstrate the influence of Abstract Expressionism. In fact, her embrace of modernity began to appear regularly in her work.

What Influenced Her Work?

In the 1960s, Kent’s art underwent profound shifts that reflected the rapidly changing world around her. In 1962, Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II) to reform the Catholic Church and make it more relevant to modern life. Kent and her fellow nuns enthusiastically embraced these changes and directed their efforts toward engaging the community around them. They focused on issues of social justice and world hunger.

Around that time, Kent encountered the work of Andy Warhol, whose thirty-two soup can paintings were exhibited at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in July 1962. It was the first Pop Art exhibition on the West Coast, and it had a noticeable impact on California artists, including Kent. This work validated Kent’s own inclination to embrace both the everyday and the divine. However, rather than copying, she created her own “spiritual Pop Art.” She combined elements of Pop Art, Vatican dogma, and her own whimsical sensibility, resulting in work that was vernacular, experimental, playful, and witty.

She depicted the chaotic visual landscape of Los Angeles. She often appropriated advertising slogans, juxtaposing them with poetry, Scripture, and song lyrics. For example, Kent repurposed Pepsi-Cola’s 1963 branding campaign—”Come Alive!”—as a spiritual directive, echoing the Bible’s miracles of resurrection while speaking in the vernacular of the time.

The act of transformation was central to Kent’s art. In addition to compelling textual pairings, she also physically altered the text itself—bending, flipping, and cropping slogans and logos to play with viewers’ expectations and make them engage with the words. Kent’s remarkable ability to see the world with fresh eyes and capture that vision in her art was noted by critics, one of whom wrote:

“Her mission, it seems, is to surprise us, to wake us up to delight.”

The Face of the Modern Nun

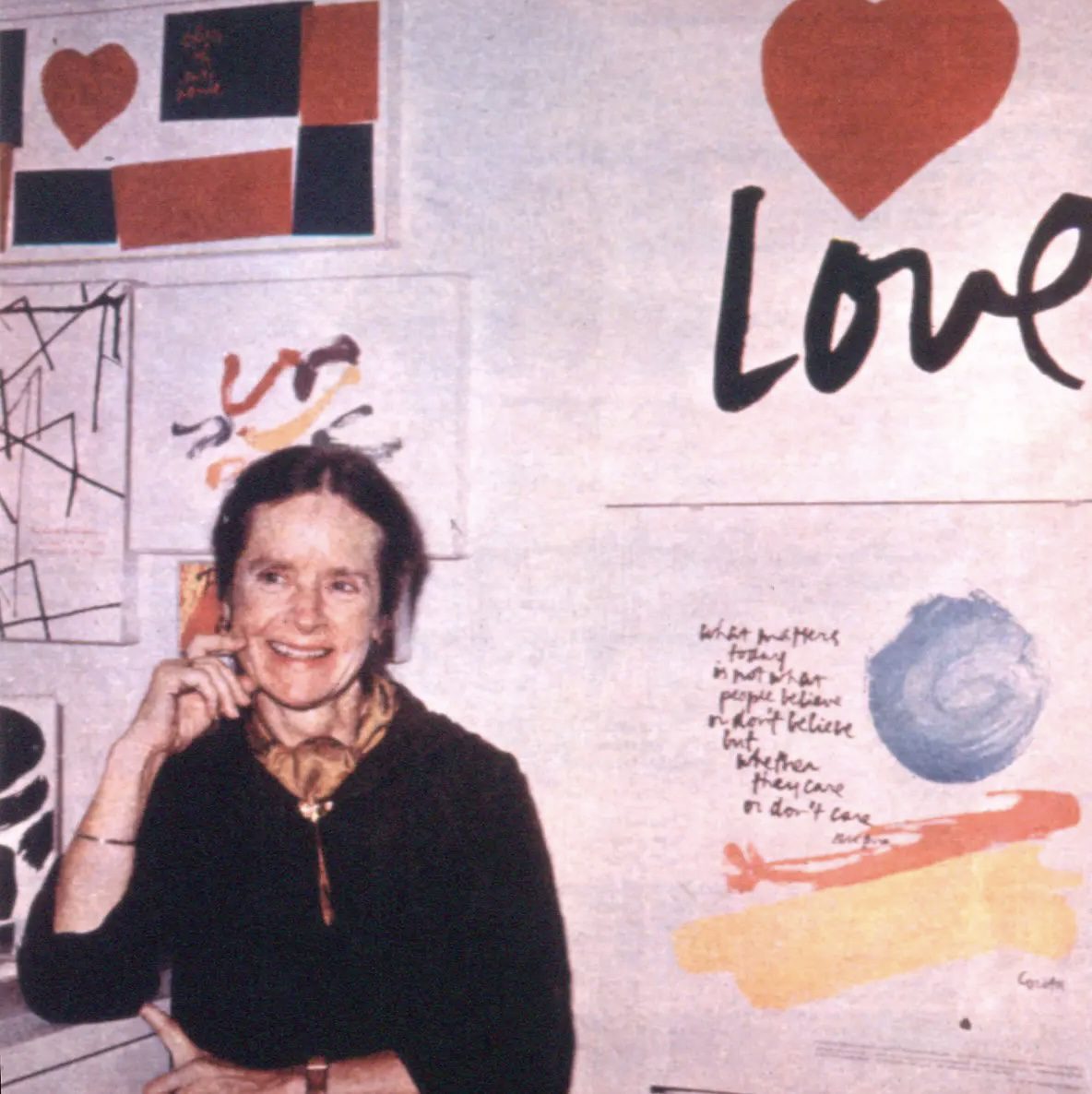

Kent also used the element of surprise to awaken her audience to issues of social justice, particularly world hunger. As the 1960s progressed, Kent’s art became more political, addressing civil rights, the Vietnam War, and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Her national and international profile soared, and she became the face of the modern nun, her image gracing the cover of Newsweek on December 25, 1967, with the headline, “The Modern Nun.”

However, within the Catholic Church, complaints mounted against her for her controversial art and teachings. For Kent, art was a vital tool for modernizing and “shaking up” the church and presenting Christian messages in a new light. Kent’s fame fueled the animosity between the progressive nuns and the conservative Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

Tensions between the order and the church leadership in Los Angeles escalated, and Sister Mary Corita left the order in 1968, returning to secular life as Corita Kent. Within a short time, most of the other Immaculate Heart sisters followed her lead. In 1969, the order separated from the church, continuing its work as an organization. Immaculate Heart College closed in 1980. In the summer of 1968, she took a sabbatical and spent the summer in Cape Cod. At the end of her leave, she realized she could not return. At age 50, Corita was living alone for the first time. She didn’t know how to drive a car or cook.

A Change in Perspective

In 1968, exhausted by her teaching schedule and tensions with Cardinal James Francis McIntyre, Kent left the sisterhood and moved to Boston. With this dramatic life change, her work became even more radical. Free from the church’s censors, Kent began to express her political views more boldly in the late 1960s. She drew attention to issues of hunger, race, civil rights, poverty, violence, and American military aggression in Vietnam. She was heavily influenced by the radical priest Daniel Berrigan, a Christian pacifist who publicly campaigned against the Vietnam War.

After a flurry of political work from 1969 into the early 1970s, Kent’s art softened considerably. Like many activists of the time, she was tired of the fight and said the time for the “physical tearing down of things” was over. Furthermore, her life became more physically challenging, as she was first diagnosed with cancer in 1974. A recurrence followed three years later. Her art underwent another crucial shift as she simplified her compositions, which now voiced universal messages of peace and personal growth. Secular texts replaced psalms and Gospels, but the spirit of hope, renewal, and transformation remained.

After 1970, her work took on an introspective style, influenced by her new environment, her secular life, and her battle with cancer. She remained active in social causes until her death in 1986. By the time of her death, she had created nearly 800 print editions, thousands of watercolors, and countless public and private commissions.

Sources: